“They get the one starving kid in Sudan that isn’t going to have a USAID bottle, and they make everything DOGE has done about the starving kid in Sudan.” — a White House official.

I’ve been a USAID contractor for most of the last 20 years. Not a federal employee; a contractor. USAID does most of its work through contractors. I’ve been a field guy, working in different locations around the world.

If you’ve been following the news at all, you probably know that Trump and Musk have decided to destroy USAID. There’s been a firehose of disinformation and lies. It’s pretty depressing.

So here are a couple of true USAID stories — one political, one personal.

The political one first. I worked for years in the small former Soviet republic of Moldova.

Moldova happened to be one of the few parts of the old USSR suitable for producing wine. The other was Georgia, in the Caucasus.

The Soviets, in their central planning way, decided that both Moldova and Georgia would produce wine — but Georgia would produce the good stuff, intended for export and for consumption by Soviet elites. Moldova would produce cheap sweet reds, which is what most Russians think wine is.

So for decades, Moldova produced bad wine and nothing but bad wine. But Russians liked it, so that was okay.

Then the USSR collapsed. And, well, Moldova continued to produce nasty cheap sweet reds, because that was all they could do. By the turn of the century, wine was Moldova’s single biggest cash export. And about 80% of that wine went straight to Russia.

This continued through the 1990s and into the early 2000s. Meanwhile, Vladimir Putin came to power in Russia. Back in 2003 or so, he wasn’t invading Russia’s neighbors… but he was already swinging a big stick in Russia’s “near abroad”, the former Soviet republics that he thought should still be under Russia’s thumb. Which absolutely included Moldova.

So whenever the Moldovan government annoyed or offended Putin… or whenever he just wanted to yank their chain… the Russian Ministry of Health would suddenly discover that there was a “problem” with Moldovan wine. And imports would be frozen until the “problem” could be resolved. Since wine was Moldova’s biggest export, and most wine went to Russia, this meant that Russia could inflict crippling damage on Moldova’s economy literally at will.

This went on for over a decade, with multiple Moldovan governments having to defer to Moscow rather than face crippling economic damage.

Enter USAID. Over a period of a dozen years or so, USAID funded several projects to restructure the Moldovan wine industry.

They brought in foreign instructors to teach modern methods. They worked with the wine-growers to develop training courses. They provided guarantees for loans so that farmers could buy new equipment. They helped Moldovan farmers get access to new varieties of grapes… you get the idea.

(By the by, the wine project was not my project. But it was literally up the street from my project. It was run by two people I know and deeply respect — one American, one Moldovan — so I had a ring-side seat for much of this.)

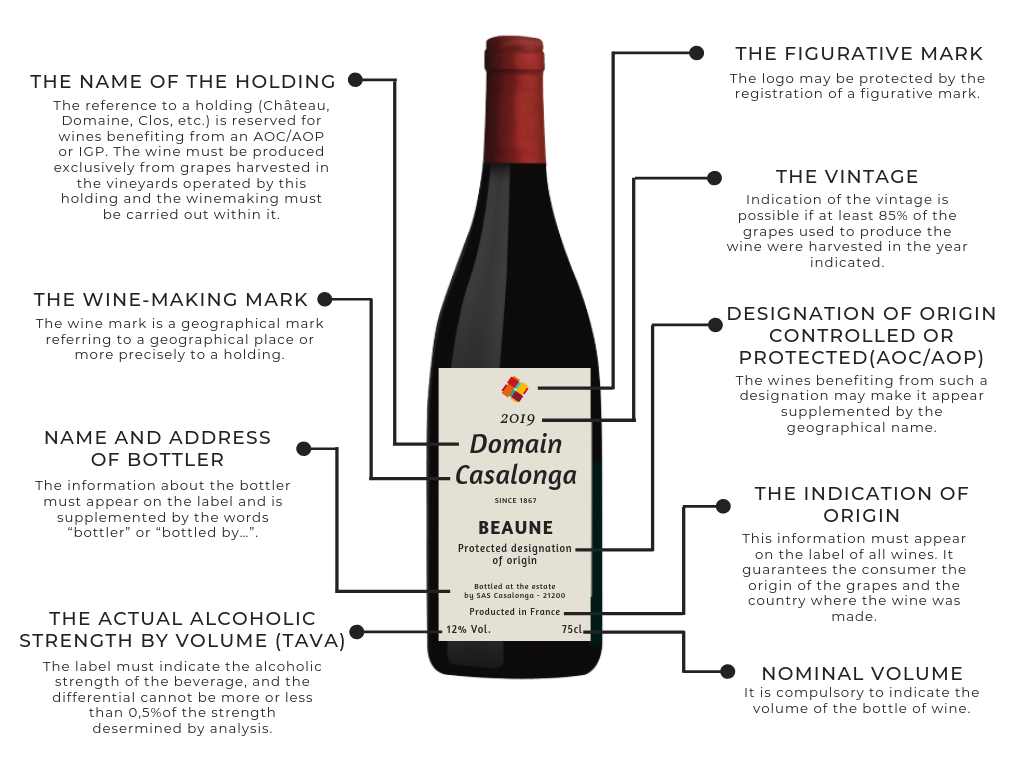

The big one was, they worked with the Moldovans on what we call market linkages. That is, they helped them connect to buyers and distributors in Europe, and figure out ways to sell into the EU. I say this was the big one, because on one hand the EU is the world’s largest market for wine! But on the other hand, exporting wine into the EU is really hard. There are a bunch of what we call NTBTs — “non-tariff barriers to trade”. For starters, your wine has to be guaranteed clean and safe according to the EU’s very high standards. That means it has to consistently pass a bunch of sanitary and health tests, and also your production methods have to be certified. Then there are a bunch more requirements about bottling, labelling and packaging.

The EU regulates the hell out of all that stuff. Like, the “TAVA” number? There’s a minimum font size for that. If you print it too small, it’ll be bounced right back to you. The glass of the bottle? Has to be a sort that EU recycling systems can deal with. The adhesive behind the label? It can be rejected for being too weak (labels fall off) or too strong (recycling system can’t remove it). There are dozens of things like that.

And then of course they had to do marketing. Nobody in Europe had heard of Moldovan wines! Buyers and distributors had to be talked into taking a chance on these new products. This meant the Moldovan exporters needed lines of credit to stay afloat. This in turn meant that Moldovan banks had to be talked into… you get the idea.

This whole effort took over a decade, from the early 2000s into the teens.

And in the end it was a huge damn success. With USAID help, the Moldovan wine industry was completely restructured. Moldova now exports about $150 million of wine per year, which is a lot for a small country — it’s over $50 per Moldovan. And it went from exporting around 80% of its wine to Russia, to around 15%. Most Moldovan wine (around 60%) now goes to the EU, with an increasing share going to Turkey and the Middle East.

(If you’re curious: their market niche is medium to high end vins du table. Not plonk, not fancy, just good midlist wines. I can personally recommend the dryer reds, which are often much better than you’d expect at their price point.)

Russia tried the “ooh we found a sanitary problem” trick one last time a few years ago. It fell completely flat. Putting aside that it was an obvious lie — if something is safe for the EU, believe me, it is safe for Russia — Moldovan wine exporters had now diversified their markets to the point that losing Russian sales was merely a nuisance. In fact, the attempt backfired: it encouraged the Moldovans to shift their exports even further away from Russia and towards the EU.

So that’s the political story. Russia had Moldova on a choke chain. Over a dozen years or so, USAID patiently filed through that chain and broke Moldova loose. Soft power in action. It worked.

Nobody knows this story outside Moldova, of course.

Okay, that’s the political story. Here’s the personal one.

Some years ago, I moved with my family to a small country that was recovering from some very unpleasant history. They’d been under a brutal ethnically-based dictatorship for a while, and then there was a war. So, this was a poor country where many things didn’t work very well.

While we were there, my son suddenly fell ill. Very ill. Later we found out it was the very rapid onset of a severe bacterial infection. At the time all we knew was that in an hour or two he went from fine to running a super high fever and being unable to stand up. Basically he just… fell over.

Wham, emergency room. They diagnosed him correctly, thank God, and gave correct treatment: massive and ongoing doses of antibiotics. But he couldn’t move — he was desperately weak and barely conscious — and there was no question of taking him out of the country. We had to put him in the local hospital for a week, on an IV drip, until he was strong enough to come home.

If you’ve ever been in a hospital in a poor, post-war country… yeah at this point someone makes a dumb joke about the NHS or something. No. We’re talking regular blackouts, the electricity just randomly switching off. Rusting equipment, crumbling concrete, cracked windows. A dozen beds crammed into a room that should hold four or five. Everything worn and patched and held together with baling wire and hope.

We’re talking so poor that the hospital didn’t have basic supplies. Like, you would go into town and buy the kid’s medication, and then you’d also buy syringes for injections — because the hospital didn’t have syringes — and then you’d come back and give those thing to the nurse so that your kid could get his medication.

In the pediatric ward, they were packing the kids in two to a bed. Because they didn’t have a lot of rooms, and they didn’t have a lot of beds. And kids are small, yeah?

But there we were. So into the hospital he went. Here’s a photo:

— Take a moment and zoom in there. Red-white-and-blue sticker, there on the bed? It says “USAID: From The American People”.

Every hospital bed in that emergency room had been donated by USAID. I believe they were purchased secondhand in the United States, where they were old and obsolete. But in this country… well, they didn’t have enough beds, and the beds that they had were fifty years old. Except for those USAID beds. Those were (relatively) modern, light and adjustable but sturdy, and easily mobile. The hospital staff were using them to move kids around, and they were getting a lot of mileage from them.

And of course, every USAID bed had that sticker on it. And so did some other stuff. There was an oxygen system that a sick toddler was breathing from. USAID sticker. Couple of child-sized wheelchairs. USAID stickers. Secondhand American stuff — USAID was under orders to Buy American whenever possible — but just making a huge, huge difference here.

As I said, it was crowded in there. Lots of beds, lots of kids, lots of anxious parents. So we got to talking with the other parents, as one does. A couple of people had a little English. And so my wife mentioned that we were here working on a USAID project…

…and god damn that place lit up like an old time juke box. “USAID!” “USAID!” People were pointing at the stickers, smiling. “USAID!” “America, very good!” “Thank you!” “USA! USA!” “Thank you!”

This went on longer than most of us would find comfortable. When it finally settled down… actually, it never really did entirely settle down. For the whole time our son was there, we had people — parents, nurses, even the hospital janitor — smiling at us and saying “USAID!” “Very good!” “Thank you!”

I’m not prone to fits of patriotic fervor. But I’m not going to lie: right then it felt good to be American.

Anyway, USAID stories. I could go on at considerable length. This is my career, after all! I could tell more stories, or comment and gloss at greater length on these.

But this is long enough already. More some other time, perhaps.

"...this five-pointed (also called five-angled) star shape is common in Populus (aspen, poplar, cottonwood) and Salix species (members of the willow family) but is also found in oaks (Quercus), and chestnut (Castanea). The pith inside a stem is made of parenchyma (large, thin-walled cells), which are often a different color than surrounding wood (xylem). The pith’s function is to transport and store nutrients. Pith is usually lighter when new, but darkens with time (as seen in images like these of cottonwood “stars”).Mowry’s story notes the importance of cottonwood to the belief systems of Native American tribes: the Lakota, the Cheyenne, the Arapaho, and the Oglala Sioux. Pacific Northwest naturalist and poet Robert Michael Pyle’s essay, “The Plains Cottonwood” (American Horticulturist, August 1993, pp.39-42), describes an Arapaho version of the story of the stars that you told above: “They moved up through the roots and trunks of the cottonwoods to wait near the sky at the ends of the high branches. When the night spirit desired more stars, he asked the wind spirit to provide them. She then grew from a whisper to a gale. Many cottonwood twigs would break off, and each time they broke, they released stars from their nodes.” Cottonwood twigs sometimes snap off without the assistance of wind, a self-pruning phenomenon called cladoptosis. Pyle suggests looking for twigs that are neither too young nor too weathered if you want to observe the clearest stars: “The star is the darker heartwood contrasting with the paler sapwood and new growth.”